philosophy

The Profession: A Business of Service

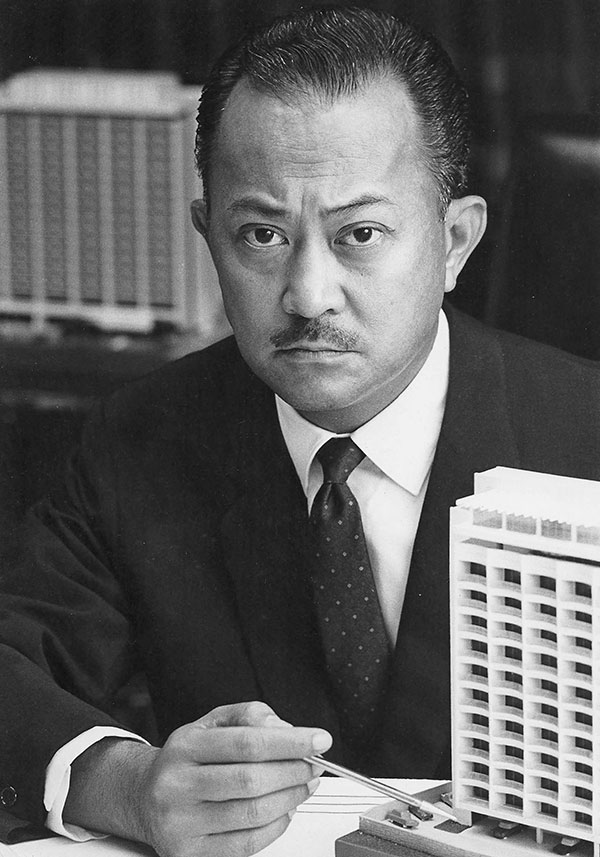

A Speech by Alfredo J. Luz Before the Pasay Rotary Club August 12, 1959

In a short talk which I was privileged to deliver before your fellow Rotarians sometime ago, I spoke on the architect and his society. Today, I should like to speak not so much as an architect but simply as a professional. My subject is not a new one. But like most simple and familiar things, it is one which is too often taken for granted and almost always forgotten. I am speaking of professionalism which, in its present sense, concerns all of us gathered here today. For a moment let us remind ourselves of those early pledges, oaths and ideals which today, after many years, lie neglected like old diplomats in dusty closets.

This is a good time for self-appraisal. The country is going through its growing pains, making mistakes and learning, developing, industrializing and keeping up with the times and the rest of the world. More schools are producing more professionals and the population is beginning to accept, need and require their services. This acceptance, however, places a greater responsibility on the professions to meet the new demands and standards of a growing and enlightened population. There is a need for new knowledge, specialization and above all, dedication to the spirit of service which is the essence of the professions.

As professionals, we are all engaged in a business of service. We provide specialized skills and knowledge, advice, opinions and information which are indispensable to present society. Through often intangible, these services can and do influence the lives, fortunes, security, well-being, pleasure and in fact the very existence of individuals or entire communities. Consider for a moment the surgeon, lawyer and engineer, and imagine their influence on countless lives in the course of their professional lives. Imagine the benefits, or consequences, as a result of their competence or ineptitude, their dedication or their indifference.

To safeguard the public’s welfare, measures have been instituted by the government for the control of companies engaged in public services and utilities. Similarly, the government insures professional competence through examinations and standards, and imposes penalties on violations of those standards. Unfortunately, the official agencies responsible for the enforcement of professional codes, standards and ethics have been ineffective and negligent, creating our present breed of pseudo-professionals who are principally dispensers of time, goods, and dubious advice. Without a firm and responsible controlling agency, the professional is left to his own devices, surviving and establishing himself on the basis of his capabilities, honesty and integrity. He sets his own standards and adheres to them to the best of his ability and conscience. The rest, unfortunately, merely survive in relative freedom, engaged in unethical practices, frenzied competition and purely commercial activity. To them honesty, integrity and dedication – the very basis of professionalism – are words which have lost all meaning, replaced by the stronger attractions of the profit motive.

This need not be the case. The public may be slow, but in time it recognizes and rewards quality. The principle of building a better mousetrap applies to goods as well as services. Learn all you can about your profession, serve the public honestly and well, and it will beat a path to your office door.

The position of trust and responsibility enjoyed by today’s professional is a reflection of man’s increasing complexity and needs in the conduct of his daily life. It came about slowly. In the beginning, man was a simple individual with few basic needs and requirements, conditioned by necessity to survive with the barest essentials. Families were independent social units, self-sufficient and isolated from other groups, requiring little in the way of goods and services. What they needed, they produced. Life was primarily existence, with little time or need for luxuries, leisure or individuality. Time has changed all of these. With great curiosity and an unlimited capacity for improvement, man in time surrounded himself with the world we now live in, with all its problems, improvements, requirements and complications. The professional grew along with it, providing some of the answers and services. New knowledge posed more difficult problems, discoveries led to improvements which in turn demanded refinements, and the professional kept ahead of the public by absorbing more knowledge and by specializing along specific lines.

Today, the professional is an expert and specialist, capable of giving sound advice and competent service. The public he serves is informed, demanding and capable of judging quality. Just as it depends on name brands and established products for assurance, so it invariably turns to professionals of proven ability for counsel and guidance.

A professional, in the widest sense, is not merely the owner of a degree but one who is a dispenser of service. In the United States, for instance, there are professional businessmen and industrialists who are as concerned about the quality of their products and services as they are about profits and losses. They have become institutions enjoying, and deserving, public confidence. For the true measure of professionalism is not in terms of pesos and centavos but in trust and public acceptance.

The professionals occupy a special place in their communities. They represent the cream of their group, having had advantage of higher education, careers, and a place of trust in the public mind. To those less fortunate than they are, they are held up as examples of success and their importance is magnified. Their advice is sought and trusted. They are called upon at all times to give authoritative opinions in their respective fields and to furnish responsible service to those who need them. The professional therefore, if he is to add honor to his profession and be of service to his fellowmen, is duty-bound to broaden his knowledge and improve himself so that he may better serve others. He should always conduct himself with dignity and all his actions, as a professional, should be governed by truth and fairness.

All of us gathered here today are members of one profession or other, all of them with long records of service to humanity. It is our responsibility to uphold their traditions, elevate their standards and, if possible, contribute to their development. Our mission, as professionals, is service. It is no accident that the common purpose underlying all the professions is simply – if I may borrow your motto: “Service Above Self – He That Serves Best Profits Most.”