philosophy

The Architect and his Society

A speech by Alfredo J. Luz Before the Manila Rotary Club May 21, 1959

When I was asked to come before Rotary today to speak on architecture, I immediately jumped at the opportunity, although I am aware of certain difficulties that I shall have to overcome in connection with this appearance. I have often wondered why a course in public speaking is not included in most curricula on architectural education, for ever since I started the practice of architecture some ten years ago, I have found myself constantly talking on a subject that is much taken for granted and, to my disappointment, not sufficiently understood.

But then architecture is a subject that is easy to misunderstand. Its effect on our daily lives is not direct; it is subtle. Whereas we cannot possibly exist without buildings, we tend to minimize the importance of order and beauty, qualities we always want associated with our buildings. Another reason for the lack of understanding is the broadness of architecture as a subject and, therefore, the lines that define it are hard to establish. Architecture stands astride two great fields of human endeavour – the artistic and the scientific. It is a compromise subject and as such finds itself in the lonely position of being neither here nor there. The artistic field frowns on architecture as being too practical, and to the scientific, it is too idealistic. If architecture, therefore, is not wholly acceptable to either of those two great fields, upon whose laws those of architecture are also based, then one can see why it is so easily misunderstood. Architecture is really a fairly simple thing, if one were only to take the trouble of learning more about its background so as to develop the proper perspective from where it can be viewed.

Architecture is an art and a science. It is the art and the science of building, and buildings serve three purposes – to meet the social and economic needs of living; to delight the senses; and last but not least, to symbolize all that man aspires to hold and to command.

Frank Lloyd Wright, the noted American architect, once said that “... architecture is the greatest of all human documents, and the most reliable record of time, place and man.”

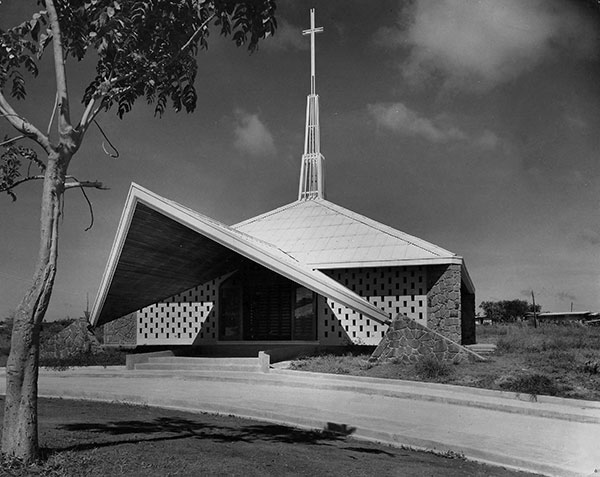

Architecture is the perfect expression of the time in which it was built, not only of the time’s artistic and scientific skill, but if interpreted correctly, of its religion, its government, its economy, and even of its political theories. The over-changing American skyline tells us of the rapid changes in the life of that nation. Their cities speak of the boldness, the power, the vitality, the ingenuity, and the sense of enterprise that also describes the American character. The medieval castles of Europe speak of the feudal era and the power of its princes. Their fortlike character conveys to us, through history, the struggles of their times. The great cathedrals and churches bring us stories of the great piety of their days and the great influence of the Church.

Long after we are gone, when archaeologists dig up the foundations of the housing projects that we see around us today, they will tell the story of the democratization and the socialization of our present society. They will convey the story of the lives of our working people, how they lived, and what was done for them by our society.

The first buildings were probably erected with very little conscious intent. They were the spontaneous consequence of man’s need for shelter against the elements and the wild animals. Buildings from the start served for nothing but utility until the builder sensed that these could also be shaped by the need for expression. It was at this point that the science of building became the art of architecture. Much later, buildings were found to reflect the time and the civilization that they served, and architecture took still another form – as a reliable recorder of history and as an influence on the present and the future. The science of building and the art of architecture had thus become a social science.

The need for architecture is as basic as the need it serves – shelter – and the claim of other professions notwithstanding, it is one of the oldest professions. At one time or another in history, the architect was actually a carpenter, mason, sculptor, artist, engineer or master-builder. It was not until recent history, at the time of the industrial revolution, that architecture was formalized as a profession. With the increased pace in construction, time became an important element and the need for specialists in building became eminent.

Today, our rapidly changing times bring us a wider knowledge of the factors affecting architecture so that modern architecture has become a dynamic study of a subject so much more alive than the architecture of the past, and which continues to change and grow with each new discovery.

Beneath the simplicity of design of the modern building is a complex process of planning, designing and coordination, so that architecture is no longer the work of any one master designer and builder, as in the past. It has become the product of the well-coordinated effort of a group of specialists who approach the solution of the different parts and aspects of modern architecture on the same uniform level of skill and competence.

The modern architect is no longer merely a creator of ideas; he must also be an able coordinator and executive. He coordinates the work of more than a dozen trades and skills, and since his works are measured in terms of actual buildings, he must be as effective in execution as he should be rich in ideas.

The modern architectural office is no longer merely a studio. It is also a well-equipped and efficiently-operated office where the technical problems of the profession are handled with competence and precision, and where the complex business of translating the architect’s ideas into actual buildings is dispatched with the same measure of promptness and efficiency as in any other business office. Today, that is what architecture has finally become – a business of service, a profession.

The professional, as we know him today, represents groups of individuals who have had the advantage of more intensive search along special lines, and who have taken upon themselves the responsibility of dispensing such knowledge for the general benefit of society. The essence of professionalism, therefore, is Knowledge, Responsibility, and Service. The architect, as a professional, fully subscribes to these conditions of professionalism and in so doing contributes his share to the betterment of his society. His work brings man into closer harmony with his surroundings and transforms his aspirations and hopes into concrete and pleasing forms.

The architect’s work places him in the triple role of artist, engineer, and social scientist. As an artist, he creates forms that will strike the proper chord in man’s heart. As an engineer, he uses the resources of the earth, and within the limits of his knowledge, builds for permanence, making every part of his structure serve to its fullest measure. As a social scientist, he probes deeply into man’s needs and problems, and provides surroundings that will permit him to develop to the fullest extent – in comfort, harmony, and beauty.

Perhaps in our present-day preoccupation over the moral and economic stability of our country, the architect’s contribution can best be appreciated in terms of what he does to increase productivity whenever he designs efficient working spaces for commerce and industry; of what he does to conserve capital and stretch building funds whenever he saves space, time, materials and labor through his designs; of what he does to improve the manufacture of construction materials by setting higher standards for their acceptability, and by suggesting how such standards can be met; of what he does to elevate the standard of living merely by spreading the benefits of design, planning and sociological research among more people; of what he does to improve mental health whenever he introduces order and beauty in the course of his work; and perhaps the architect can best be judged by what he does to strengthen the moral fiber by merely being another professional trying to establish and practice some norm of ethical standard which is so sorely lacking now.

The practice of architecture is a rewarding experience. The architect enjoys a deep satisfaction in the knowledge that he serves an indispensable need of society. He brings the benefits of technology to problems that seem purely social or aesthetic, and uses the humanizing influence of art in undertakings that are purely technical and commercial. The world, through his art and his science, becomes a better place to live and work in. But the architect’s greatest source of inspiration comes from the belief and the hope that his work, which is totally constructive, is part of man’s growth and progress, a document of his time and, in the supreme instance, possibly a contribution to the future.